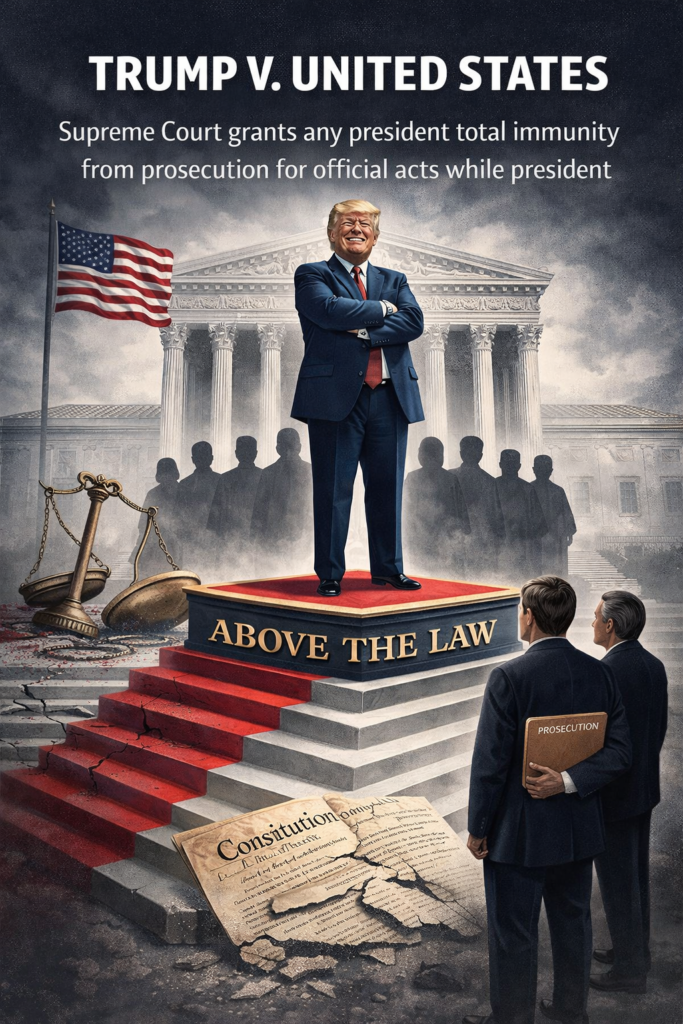

Presidential Immunity

Trump v. United States (2024) represents one of the most significant Supreme Court decisions in modern American history. In a 6-3 ruling along partisan lines, the Supreme Court ruled that the President of the United States has absolute immunity for all official acts committed while in office. Essentially, the President is above the law.

The case arose from Special Counsel Jack Smith’s federal indictment of former President Donald Trump on four counts related to alleged attempts to overturn the 2020 presidential election results. The majority opinion, authored by Chief Justice John Roberts and joined by Justices Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, and Kavanaugh (with Justice Barrett joining in part), established a three-tiered framework for analyzing presidential conduct:

core constitutional powers deserving absolute immunity,

official acts warranting presumptive immunity, and

unofficial acts receiving no immunity.

How the Supreme Court Betrayed American Democracy

In Trump v. United States, six justices invented a doctrine of presidential immunity that appears nowhere in the Constitution, contradicts the Founders’ explicit intentions, and places the President above the law. This decision doesn’t just protect Donald Trump, it permanently transforms the American presidency into something the Framers explicitly rejected: an elected monarchy immune from criminal accountability.

A Constitution Rewritten by Judicial Fiat

The Constitution says nothing about presidential immunity from criminal prosecution. When the Framers wanted to grant immunity, they did so explicitly; the Speech or Debate Clause protects members of Congress. They deliberately chose not to extend similar protection to the President. During the ratification debates, Founders like James Iredell assured Americans that presidents would be ‘punishable by the laws of his country’ and ‘not exempt from a trial.’ The entire American experiment was premised on rejecting the British model, where the king could do no wrong.

Yet the Roberts Court, in its wisdom, decided it knew better than the Constitution’s authors. The majority fabricated a three-tiered immunity framework from whole cloth: absolute immunity for ‘core constitutional powers,’ presumptive immunity for ‘official acts,’ and no immunity only for ‘unofficial acts.’ This framework sounds reasonable until you realize what it means in practice. Almost everything a president does can be characterized as official. And the Court prohibited prosecutors from even examining the president’s motives or using evidence of official acts when prosecuting unofficial conduct. The result? Presidential accountability has been gutted.

The Invitation to Tyranny

Justice Sotomayor didn’t mince words in her dissent: ‘Orders the Navy’s Seal Team 6 to assassinate a political rival? Immune. Organizes a military coup to hold onto power? Immune. Takes a bribe in exchange for a pardon? Immune.’ These aren’t hypothetical scare tactics; they’re logical applications of the majority’s reasoning. If the President uses his official powers, even for manifestly corrupt purposes, he cannot be criminally prosecuted.

The pardon power is official, so selling pardons is immune. Control over the military is official, so ordering unlawful military action is immune from liability. Supervision of the Justice Department is official, so obstructing investigations is immune.

The Court’s defenders claim impeachment provides accountability. Impeachment is a political process requiring a two-thirds Senate supermajority—a threshold that makes conviction nearly impossible in our polarized era. Trump himself was impeached twice and acquitted both times despite overwhelming evidence of misconduct. Impeachment wasn’t designed to be the sole check on presidential criminality; it was meant to supplement criminal law, not replace it. The Constitution’s Impeachment Judgment Clause explicitly states that impeachment doesn’t preclude criminal prosecution; the Framers expected both mechanisms to exist.

Democracy’s Loaded Weapon

This decision hands every future president a loaded weapon. It tells them: use your official powers however you wish, and the criminal law cannot touch you. The only constraint is political, and political constraints have proven woefully inadequate.

The evidentiary prohibition makes matters worse. Even when prosecuting supposedly private conduct, prosecutors cannot introduce evidence of the president’s official actions. This means they cannot show the broader criminal scheme, cannot prove corrupt intent, and cannot connect the dots between public actions and private crimes. Presidential corruption will become nearly impossible to prove, even when it’s obvious to everyone.

The End of ‘No One Is Above the Law’

For 235 years, America operated on a foundational principle: no person is above the law. Presidents could be prosecuted for crimes. Richard Nixon accepted a pardon because he understood he faced criminal jeopardy. Bill Clinton carefully navigated legal landmines during the Lewinsky scandal. Even if no president had previously been prosecuted, the threat existed and mattered.

Trump v. United States shatters that principle. It creates, for the first time in American history, a class of one, the President, who operates outside the criminal law for official actions. Justice Jackson was right: this ‘Presidential accountability model’ abandons individual accountability in favor of something alien to our constitutional tradition. It shifts America away from the rule of law toward rule by law, where law applies to everyone except the one wielding supreme executive power.

Why This Matters Now

Some argue this decision merely clarifies existing norms and won’t change presidential behavior. The decision provides legal cover for conduct that would have been unthinkable before. It removes the deterrent effect of criminal law for a wide swath of potential presidential misconduct. And it sends an unmistakable message: if you can frame your corruption as an official act, you’re untouchable.

The timing makes this especially perilous. This ruling comes as American democracy faces genuine threats, election denial, political violence, and the erosion of democratic norms. We needed the Supreme Court to reinforce constitutional guardrails. Instead, it removed them. The Court has given future presidents a roadmap for authoritarian action: ensure you use official powers, and criminal law cannot stop you.

A Republic, If We Can Keep It

Benjamin Franklin warned that the Founders had created ‘a republic, if you can keep it.’ The Supreme Court has made it dramatically harder. By exempting presidents from criminal accountability for official acts, the Court invites abuse of power. By prohibiting the use of official acts as evidence, it ensures such abuse will go unpunished. Grounding this immunity in constitutional interpretation rather than statute, it makes correction nearly impossible without a constitutional amendment.

Justice Sotomayor closed her dissent with unprecedented words: ‘With fear for our democracy, I dissent.’ That fear is justified. This decision doesn’t just affect Donald Trump’s prosecution; it reshapes the presidency itself, transforming it into an office that can wield immense power with minimal legal accountability. The Framers designed a president who would be subject to law. The Supreme Court has created something closer to a king.

The question now is whether the American people will accept this transformation, or whether they will demand that their elected representatives restore the principle that made America exceptional: that in this nation, no one, not even the President, is above the law.

Time to reform the Supreme Court

Nine individuals, appointed for life, holding more power over your daily existence than almost any elected official you’ll ever vote for. They decide whether you have access to healthcare, what rights you can exercise, how your vote counts, and what protections you’re guaranteed under the law.

Yet unlike every other judge in America, they answer to no code of ethics. Unlike any other public servant, they serve until they choose to retire or die. And unlike the officials you elect, you have little say in who they are.

This is the reality of the United States Supreme Court. And it’s time we had an honest conversation about why that’s a problem, and what we can do about it.

Resources:

SCOTUS decisión: https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/23pdf/23-939_e2pg.pdf

Oral Arguments: https://www.supremecourt.gov/oral_arguments/audio/2023/23-939

Transcript of Oral Arguments: https://www.supremecourt.gov/oral_arguments/argument_transcripts/2023/23-939_3fb4.pdf